The End of Gigafactories? Exploring Local Energy Manufacturing

A Thought Experiment in Community-Scale Energy Independence

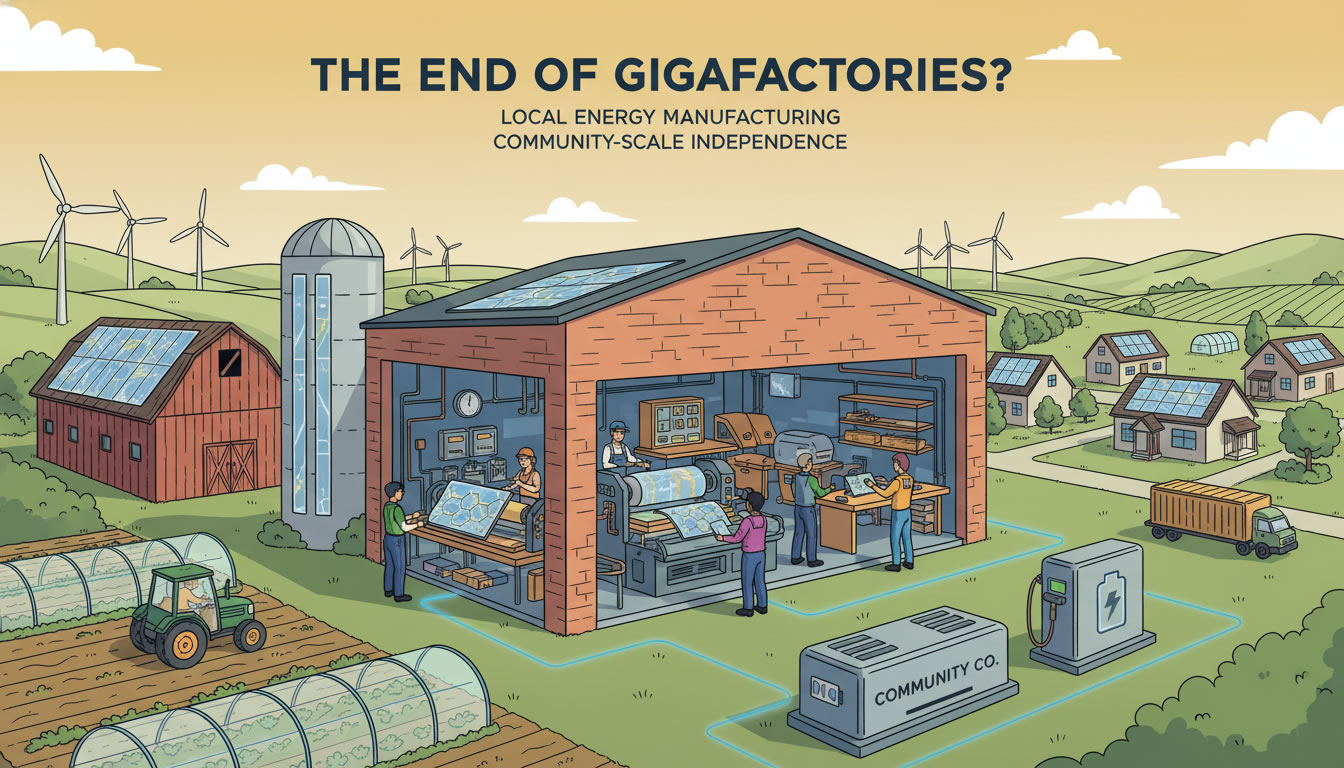

What if a community of a few thousand people could manufacture their own solar panels and batteries? Not assemble components shipped from overseas, but actually manufacture the energy collection and storage infrastructure itself, using equipment that costs roughly what a small business might invest in a commercial kitchen or light manufacturing setup.

Listen here:

This isn’t science fiction, but it’s not quite reality either, at least not at scale. It’s a thought experiment grounded in emerging technologies that seem to be lowering the barrier to entry for energy manufacturing from “build a billion-dollar gigafactory” down to “equipping a modest facility with a few hundred thousand dollars of gear and train a small team.” Whether this specific vision materializes or not, exploring what it could mean helps us think about the kind of energy future we might want to build.

The Gigafactory Problem

Right now, if you want energy independence, whether you’re a rural community, an island nation, or a city trying to transition away from fossil fuels, you have essentially two choices. You can buy solar panels and batteries manufactured in massive centralized facilities that cost billions to build and require global supply chains to feed, or you can do without. There’s no middle path. The economics of silicon solar panel production and lithium-ion battery manufacturing demand scale. You need gigafactories because the processes themselves require it.

This creates a particular kind of lock-in. Communities that want to control their energy future can’t actually manufacture the infrastructure themselves. They can install it, maintain it, even finance it locally. But the manufacturing happens elsewhere, controlled by whoever can muster the capital for gigafactory construction. And with that manufacturing control comes a whole cascade of dependencies: on global supply chains, on corporate R&D priorities, on whatever environmental standards (or lack thereof) govern those distant facilities, on geopolitical stability in regions you have no influence over.

A Different Path Emerges

But what if the chemistry could be different? What if instead of requiring high-temperature vacuum deposition and precision silicon wafer fabrication, solar panels and batteries could be printed using room-temperature processes similar to commercial printing? Several small companies and research groups have been exploring exactly this possibility, using organic photovoltaics and printable battery chemistries that sidestep the gigafactory requirement entirely.

The vision looks something like this: A facility roughly the size of a commercial print shop, equipped with roll-to-roll printing equipment and coating systems, operated by a team of two to five people with training comparable to skilled manufacturing technicians. The equipment investment ranges from about seventy thousand to two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. That’s significant, but within reach of community investment, small business loans, or cooperative financing. The same facility can manufacture both solar panels and battery cells using similar processes, similar supply chains, and the same workforce skills.

What This Looks Like on the Ground

Imagine a rural agricultural community in the Midwest, a few thousand people spread across farmland and a small town center. The local economy has traditionally revolved around farming, but young people have been leaving for decades because there aren’t enough jobs. The community decides to invest in local energy manufacturing.

They convert an unused warehouse near the town center into a manufacturing facility. A local team gets trained on the printing equipment, skills not unlike those needed for commercial printing or light manufacturing work that already exists in many small towns. The facility starts producing solar panels during the spring and summer months when installation demand is highest. Farmers install the panels in their fields or on barn roofs, generating power for their operations and selling excess back to the local grid. Come winter, when solar installation slows down, the facility shifts production to battery cells, building out the community’s energy storage capacity to handle the seasonal variation in solar generation.

The same scenario works differently for an island community. Islands typically pay premium prices for imported energy, whether that’s diesel fuel shipped in for generators or components for renewable installations. Every battery cell and solar panel that doesn’t have to arrive by ship or plane represents real cost savings. More importantly, it represents resilience. When the next hurricane hits, the community doesn’t wait for replacement components to be manufactured overseas, shipped to a mainland port, and then ferried out. They manufacture replacements locally as soon as the facility is back online. They might even maintain a containerized backup manufacturing system that can be stored in a protected location and deployed rapidly after disaster strikes.

Or consider a former industrial town where the main employer shut down operations and moved manufacturing overseas. The workforce knows manufacturing. They have the skills, they understand process control, they’re used to shift work and quality standards. A local manufacturing facility doesn’t just provide energy infrastructure; it provides skilled jobs and economic agency. The community gets to decide whether to optimize for maximum efficiency, prioritize environmental sustainability even if it costs a bit more, or experiment with new approaches that larger manufacturers might consider too risky.

One Example: Calixarene-Based Printing

To make this concrete, consider one example technology that researchers have been exploring: calixarene-based battery chemistry combined with printable organic photovoltaics. Calixarenes are large cup-shaped molecules that can trap lithium ions, potentially enabling battery chemistry that works at room temperature and could be formulated with water-based solvents instead of the toxic organic solvents used in conventional lithium-ion production. The same general approach to printable, room-temperature processing could apply to organic solar cells, where light-sensitive polymers are deposited in thin layers using coating or printing techniques.

The key insight isn’t necessarily that calixarene specifically will be the breakthrough that enables all this. It’s early research, and there are significant unknowns about longevity, performance at scale, and whether the theoretical advantages actually pan out in practice. But calixarene is one of several research directions all pointing toward the same possibility: that energy collection and storage don’t have to be locked into the high-capital, high-temperature, toxic-chemistry paradigm that currently dominates. Whether it’s calixarene or some other printable chemistry that ultimately succeeds, multiple groups are finding ways to lower the barrier to entry below the gigafactory threshold. That’s what matters for this thought experiment.

What Distributed Manufacturing Enables

If communities could actually manufacture their own solar panels and batteries, what does that change?

Economic Democratization: The capital barrier drops from billions to hundreds of thousands. That puts it within reach of communities that have been entirely locked out of energy manufacturing. It means the jobs stay local, the profits recirculate locally, and economic decisions about the energy system are made by people who actually live with the consequences. A farming community can decide to optimize for seasonal flexibility, building more batteries to store summer solar for winter use. An island can prioritize resilience and local sufficiency over maximum efficiency.

Environmental Agency: When communities control manufacturing, they can choose sustainability even when it costs performance. Traditional solar and battery manufacturing is locked into toxic processes by the physics of the materials. You can’t make silicon solar cells without high temperatures and hazardous chemicals, and lithium-ion batteries require toxic organic solvents. But printable organic technologies could potentially be formulated with water-based solvents and biodegradable binders if communities demand it. Yes, that might mean accepting slightly lower efficiency or shorter lifespan. But unlike with silicon and lithium, where you’re stuck with whatever processes work at all, printable chemistry offers design choices. Communities can decide they’d rather design for deconstruction now than find themselves hip-deep in toxic waste in forty years.

Disaster Resilience Through Mutual Aid: When manufacturing is distributed across many communities, disaster response looks completely different. A hurricane devastates a coastal region, knocking out power infrastructure. In the current paradigm, recovery depends on global supply chains restarting, components being manufactured overseas and shipped in, installation crews arriving from other states. But in a distributed manufacturing world, neighboring communities that weren’t hit can load containerized manufacturing equipment onto flatbed trucks, drive it into the disaster zone, and start producing temporary solar panels and battery systems to restore basic power. When that community recovers, the mobile equipment moves on to the next disaster, or back into storage until the next hurricane season, or gets loaned to a community across the country dealing with wildfire recovery.

This isn’t charity. It’s mutual aid among communities that understand they’re all vulnerable to different disasters and all benefit from distributed manufacturing capacity. The island community helps the coastal town after a hurricane; the coastal town helps the farming community after a derecho; the farming community helps the mountain town after wildfires. The system becomes resilient not through massive centralized redundancy but through distributed capacity and community cooperation.

Innovation at the Edges: When thousands of communities operate manufacturing facilities, you get thousands of natural experiments. One community discovers that local agricultural waste can be processed into biodegradable binder materials, reducing dependence on imported chemicals. Another figures out that their particular climate allows for a formulation that prioritizes longevity over peak efficiency, extending panel life from ten years to fifteen. A third develops a recycling process that recovers ninety percent of materials for reuse in new panels. These innovations don’t emerge from corporate R&D labs focused on quarterly earnings. They emerge from communities solving local problems and then sharing solutions with other communities facing similar challenges.

Political and Economic Implications: The shift from gigafactory dependence to distributed manufacturing fundamentally changes who controls energy infrastructure. Right now, energy independence is constrained by capital. You need billions to build the manufacturing base, which means only governments, large corporations, or wealthy nations can play. But if the barrier drops to hundreds of thousands, communities can opt out of that system entirely. A region decides it doesn’t like the environmental practices of the major solar manufacturers, so it builds its own facility and chooses cleaner formulations. A country facing sanctions or trade restrictions manufactures its own energy infrastructure rather than remaining dependent on imports.

This distributes not just manufacturing capacity but political power. It makes energy systems harder to control centrally, harder to disrupt strategically, and more responsive to local priorities than corporate incentives.

The Choice Ahead

None of this is inevitable. The technologies that could enable community-scale manufacturing are still emerging. We don’t yet know if printable organic solar cells will ever match silicon’s efficiency, or if calixarene batteries (or whatever alternative chemistry succeeds) will prove durable enough for decade-long deployments. We don’t know if the economics will actually work at community scale, or if manufacturing challenges that look solvable in research labs will prove intractable in real-world production facilities run by small teams.

But even if the specific technologies change, the core question remains: What kind of energy future do we want to build? Do we want energy manufacturing to remain concentrated in gigafactories that require billion-dollar capital investment and global supply chains, controlled by whoever can muster that capital? Or do we want to push toward distributed manufacturing that puts control in the hands of communities, even if it means accepting some tradeoffs in efficiency or performance?

This is a choice we can make, not something determined purely by physics or economics. We can choose to research printable chemistries that work at community scale. We can choose to prioritize sustainability and local recyclability even when it costs performance. We can choose to build mutual aid networks for disaster response rather than assuming centralized supply chains will always restart quickly enough. We can choose to value local economic control and community agency alongside pure efficiency metrics.

The gigafactory era solved certain problems. It scaled up renewable energy production dramatically and drove costs down through massive economies of scale. But it also locked us into centralization, global supply chains, and dependence on whoever controls the capital for gigafactory construction. As new technologies emerge that might offer a different path, we get to ask: Is that centralization actually serving us? Or would we rather build a future where communities can manufacture their own energy infrastructure, make their own choices about sustainability and performance tradeoffs, and help each other through disasters using distributed manufacturing capacity instead of hoping global supply chains restart quickly enough?

The post-gigafactory era isn’t here yet. But we can start asking what we’d want it to look like if it arrives, and what choices we need to make now to build toward that vision rather than merely replicating centralization at a smaller scale.

References:

- Ziroth’s video on the battery Technology (YouTube)

- Two-Bit Davinci’s video on the battery technology (YouTube)

- Undecided with Matt Ferrell (YouTube)

- Donut Lab

- Nordic Nano